- The Wall Street Journal – Jon Hilsenrath: Atlanta Fed’s Lockhart: Fed Is ‘Close’ to Being Ready to Raise Short-Term Rates

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta President Dennis Lockhart said the economy is ready for the first increase in short-term interest rates in more than nine years and it would take a significant deterioration in the data to convince him not to move in September. “I think there is a high bar right now to not acting, speaking for myself,” Mr. Lockhart said in an exclusive interview with The Wall Street Journal. He is among the first officials to speak publicly since the Fed’s policy meeting last week, at which the central bank dropped new hints that a rate increase is coming closer into view, a point he sought to underscore. Mr. Lockhart is watched closely in financial markets because he tends to be a centrist among Fed officials who moves with the central bank’s consensus, unlike those who stake out harder positions for or against changing interest rates. His comments are among the clearest signals yet that Fed officials are seriously considering a rate increase in September.

Comment

<Click on graphic for larger image>

So why is the Fed targeting the fed funds market? While never stated directly, we believe the Fed is doing it for two reasons. First is tradition – most people are accustomed to looking at the fed funds rate. Second is the belief that when the Fed’s balance sheet and interest rates return to “normal,” the funds rate will become relevant again.

That said, lack of liquidity in the funds market does pose a significant challenge. Ben Bernanke even suggested the Fed consider dropping the fed funds rate as its benchmark. From Bernanke’s April 15, 2015 blog:

Moreover, the fed funds market is small and idiosyncratic. Monetary control might be more, rather than less, effective if the Fed changed its operating instrument to the repo rate or another money market rate and managed that rate by its settings of the interest rate paid on excess reserves and the overnight reverse repo rate, analogous to the procedures used by other central banks.

Why Is The Fed Funds Market Disappearing?

Banks are required to hold reserves in an account with the Federal Reserve. The Fed has the ability to add or drain money from these accounts via open market operations. The fed funds market is where banks trade excess reserves with each other. Banks that are under-reserved borrow funds from banks that over-reserved. Every other Wednesday banks must balance their accounts.

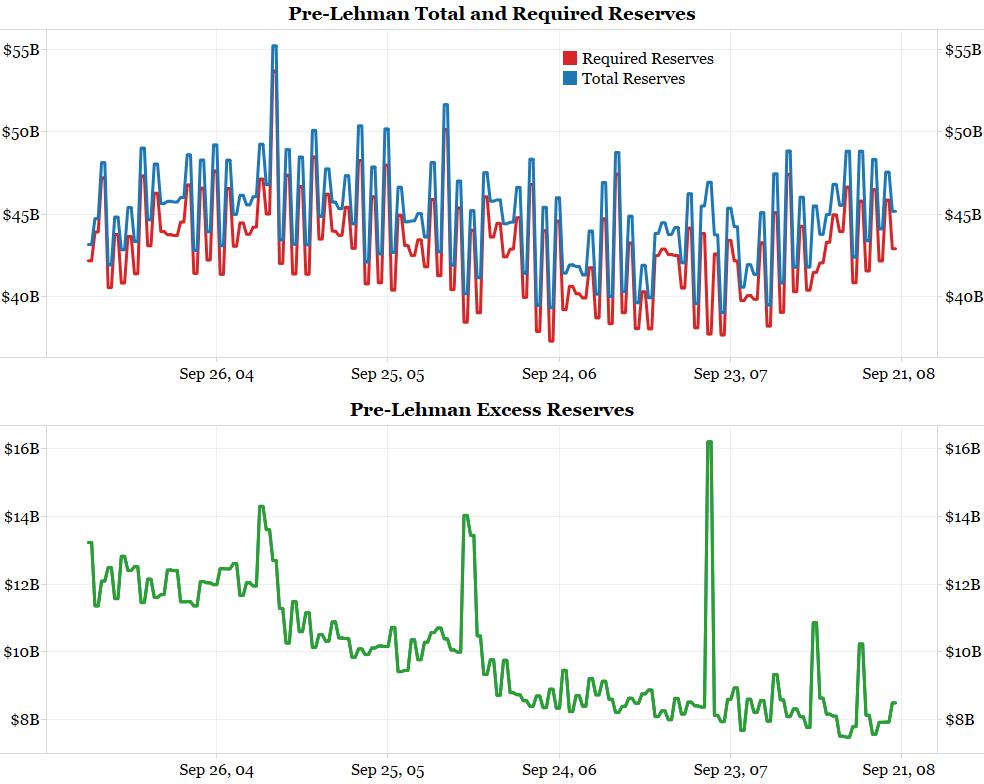

The blue, red and green lines in the chart below show the total, required and excess reserves held in all accounts at the Federal Reserve. This chart ends on September 15, 2008 to highlight the “pre-Lehman era.”

Back then total (blue) and required (red) reserves were around $45 billion and excess reserves (green) were around $8 to $10 billion. In these days if the Fed wanted the fed funds rate to go up, they would drain a few billion from total reserves, effectively reducing excess reserves. This shortage would drive up the cost of reserves, the fed funds interest rate.

<Click on chart for larger image>

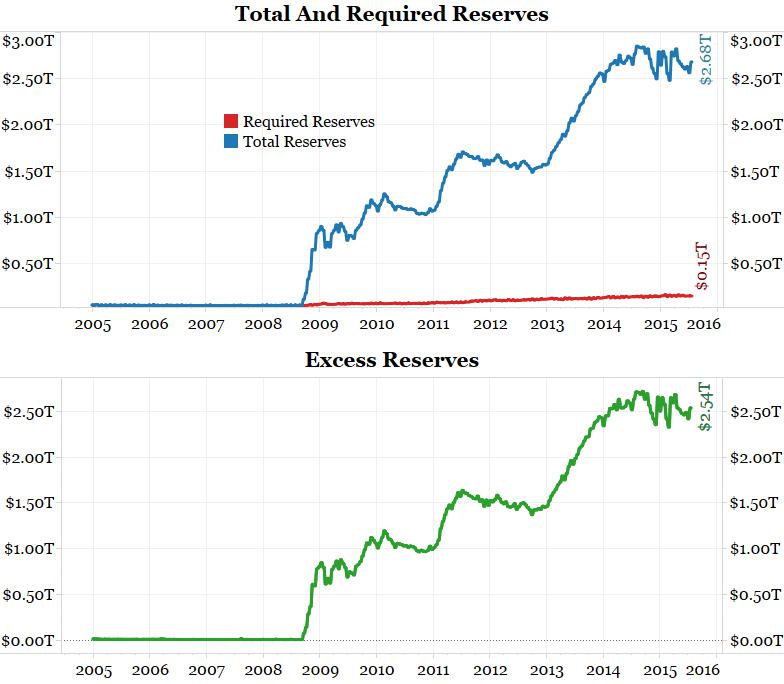

Once the financial crisis hit, the Fed started offering emergency loans to the banks followed by various rounds of QE (i.e., bond buying with “printed money”). The chart below shows the pre – and post-Lehman era of the same chart above.

While required reserves went from $47.1 billion to $138.8 billion, total reserves shot up from $42 billion to $2.68 trillion. Excess reserves went from $14.3 billion to $2.54 trillion.

The U.S. banking system has thousands of banks with over $11 trillion in assets. Pre-Lehman, these banks traded about $10 billion in excess reserves with each other in order to balance their accounts every two weeks (bank statement period). Today every bank is collectively massively over-reserved by trillions thanks to the QEs and has no need for the fed funds market. The reason the fed funds market exists at all is because the GSEs (FHLB, Fannie and Freddie) and foreign banks that do not have reserve accounts with the Fed can access it for funding. However, as shown in the chart above, the fed funds market is a small fraction of its former self.

<Click on chart for larger image>

How Will The Fed Target The Fed Funds Market

From the July 29-30, 2014 FOMC minutes statement:

Participants agreed that adjustments in the IOER [Interest On Excess Reserves] rate would be the primary tool used to move the federal funds rate into its target range and influence other money market rates. In addition, most thought that temporary use of a limited-scale ON RRP [overnight fixed-rate reverse repo] facility would help set a firmer floor under money market interest rates during normalization. Most participants anticipated that, at least initially, the IOER rate would be set at the top of the target range for the federal funds rate, and the ON RRP rate would be set at the bottom of the federal funds target range.

What are these tools?

Interest On Excess Reserves Or IOER

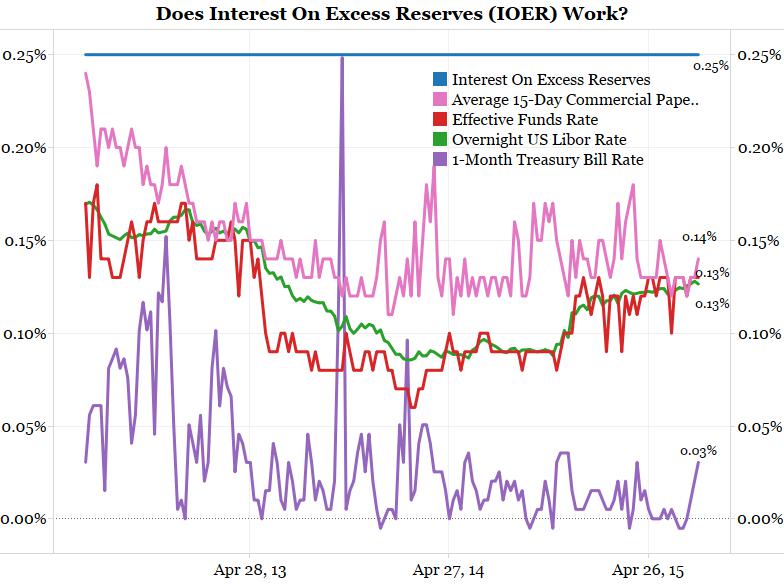

The first tool mentioned in the passage above is Interest On Excess Reserves or IOER. This is the rate the Fed pays to the banks on excess reserves (chart above, green line). So while the Fed can pay a higher interest rate on the trillions in excess reserves, no one, including the Fed, is sure this will lead all short-term rates (fed funds rate, overnight general collateral, commercial paper, Treasury Bills, etc) higher.

The blue line in the next chart is the IOER, which has been at 0.25% since December 17, 2008 (the date of the last ease of the funds rate to its current target of 0% to 0.25%). Notice that almost all major interest rates have been trading well below this target. It appears banks are sitting on their excess reserves, collecting interest income and not passing it along in the form of higher deposit rates which would influence all these market rates higher.

<Click on chart for larger image>

University of Chicago’s John Cochrane, who is a very influential economist in Fed circles, said this earlier this year:

What if the Fed announces the long-awaited interest rate rise, the Fed starts paying banks 50 bp on reserves and… nothing happens. Deposit rates stay at zero, treasury rates stay at zero. Congress notices “the Fed paying big banks billions of dollars to sit on money and not lend it out to needy businesses and households.” Mostly foreign big banks by the way. Nightmare scenario for the Fed.

Overnight Fixed-Rate Reverse Repo or ON RRP

The Fed recognized the problem with IOER and updated their thinking in their March 18, 2015 minutes:

In their discussion of the options and strategies surrounding the use of tools at liftoff and the potential subsequent reduction in aggregate ON RRP capacity, participants emphasized that during the early stages of policy normalization, it will be a priority to ensure appropriate control over the federal funds rate and other short-term interest rates. Against this backdrop, participants generally saw some advantages to a temporarily elevated aggregate cap or a temporary suspension of the cap to ensure that the facility would have sufficient capacity to support policy implementation at the time of liftoff, but they also indicated that they expected that it would be appropriate to reduce ON RRP capacity fairly soon after the Committee begins firming the stance of policy.

In September 2013, the Fed created the overnight fixed-rate reverse repo facility (ON RRP). Through this facility, the Fed offers repo transactions to money market funds. The Fed will currently give certain funds 5 basis points on any money deposited at the Fed. The draw for the funds is that the Federal Reserve is considered one of the safest counter-parties in the world. So if the banks take the extra IOER and do nothing with it, the Fed will go around the banks via its relatively new ON RRP facility and offer the a higher interest rate to everyone else.

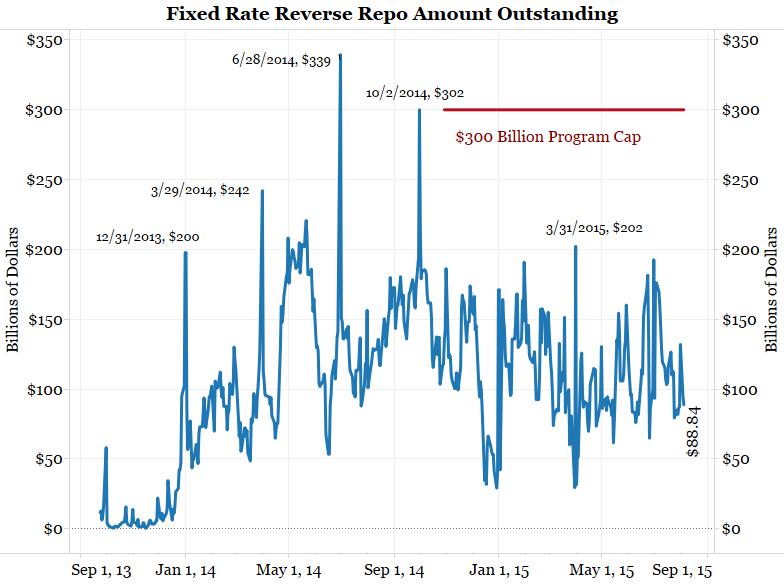

The chart below shows the trading of ON RRP since its creation.

<Click in chart for larger image>

Starting in October 2014 the Fed capped this facility at $32 billion per counter-party and $300 billion for the entire facility. This is noted in red in the chart above. Why would the Fed cap this program?

To put it bluntly, the Fed is afraid of what we have described as “the infinite black hole.” Money market funds essentially yield zero. Additionally the “breaking of the buck” by a money market fund called The Reserve Fund two days after Lehman failed (September 17, 2008) almost brought down the financial system. This remains a seminal event for the money market fund industry, one that has led to many rule changes to prevent the same thing from happening in the future.

Fund management companies do not make money on zero yielding money market funds. And attitudes among fund investors have changed since the Reverse Fund failure in September 2008. Now money fund investors are wary of any money market fund offering a yield significantly higher than its peers. It is looked upon as a fund that is taking too much risk and should be avoided. Fund managers continue to offer money market funds to complete their product list but do not make money on them and devote as few resources as possible to them.

Given these new attitudes, if the the Fed is offering itself as a counter-party and a competitive interest rate, then why wouldn’t 100% of all money in these funds is go into ON RRP with the Fed? The Fed worried about this exact scenario, which is why they capped the program at $300 billion in total.

Lifting The ON RRP Cap

So if the program is capped at $300 billion and the Fed said it is a priority to ensure appropriate control over the federal funds rate and other short-term interest rates, can it still work? Is it possible T-bill yields and general collateral repo rates will stay near zero once the Fed offers a higher IOER and ON RRP rate?

University of Chicago economist John Cochrane addressed this point earlier this year:

You can also see from my story, that if the ON RRP facility is important for transmitting higher interest on reserves to other assets, the Fed might need to do a lot of it. A lot. We’re trying to raise the interest on Treasuries, Agencies, commercial paper, etc. etc. etc. by having money market funds attempt to sell those and hold reserves. They might buy a lot of reserves before rates are equalized.

Cochrane is correct. These tools will effectively move interest rates if they are done in big enough size. How big? Since this has never been tried before, nobody is really sure. Cochrane estimates this facility might have to offer several hundred billions of dollars in repos, maybe more than $1 trillion dollars.

In conclusion, although the Federal Reserve will be removing its policy accommodation in a much-changed money market environment, the Desk is ready to implement policy firming when the FOMC determines that economic and financial conditions warrant it. The minutes of the March FOMC meeting outline the Federal Reserve’s intended operational approach, and our testing program gives us confidence that we have the necessary tools to enable a smooth liftoff. The minutes highlight that policymakers will be particularly careful at the start because demonstrating appropriate control over the federal funds rate and other short-term rates is a priority. This may entail elevated aggregate capacity in an ON RRP facility at liftoff because we don’t know how much support we are currently getting from the zero lower bound, which creates some uncertainty about the demand for ON RRPs. However, the ON RRP will be used only to the extent necessary for monetary policy control because it has some potential financial stability and footprint costs associated with it. Moreover, the Federal Reserve has a number of backup tools should things work differently than expected, and policymakers will make changes as necessary as normalization proceeds.

In short, when the Fed signals it is going to raise rates, it is critically important they show they have control over short-term interest rates. When the Fed signals interest rates are to rise 25 basis points, all short-term interest rates need to rise 25 basis points. The Fed intends to accomplish this by offering higher ON RRP rates in large enough size to compete with other money market rates.

This is where the infinite black hole argument comes into play. If ON RRP expands too much it instantly becomes a significant part of the short-term interest rate market. Other short-term rates could go begging. This could cause financial stability issues.

But, if the Fed does not expand the ON RRP enough, short-term interest rates don’t move up with the Fed’s announcement and the Fed looks like they have lost control. So how big should this facility be? No one knows since it is less than 2 years old and such a tool has never been used.

The FOMC is worried about this. From the January 28, 2015 FOMC minutes:

A couple of participants expressed continued concerns about the potential risks to financial stability associated with a large ON RRP facility and the possible effect of such a facility on patterns of financial intermediation

Conclusion

This brings us back to our original question – why is the fed funds futures curve diverging so much from Fed expectations? The simple answer is the market does not believe the Fed will follow through with their time table for rate hikes.

Could the subtle answer be the markets are afraid the Fed may be too timid to raise the ON RRP cap to move short-term interest rates, including the fed funds rate? Could economists be correct that the Fed is going to announce a rate hike in September while the market could be correct that rates will only rise a fraction of that 25 basis point announcement?

If so, how will market participants interpret this?

Yesterday we highlighted the different ways to calculate the probability of a Fed hike in September. We found the probability of a September rate hike to be less than 50% using the two most popular calculation methods (Bloomberg and the CME). We also pointed out the forward rate for fed funds usually over-predicts a rate hike, meaning it often predicts rate hikes when none happen. This makes the lack of market conviction on a rate hike all the more puzzling in the face of Fed assurances that the September meeting will commence liftoff.

The story above is the latest in a litany of Fed speeches on the likelihood of a September hike. The Fed could not be more clear in their intention, yet the market does not seem to be listening.

With this is mind, we want to make the argument that maybe both the economists and the markets could be correct. Economists could be correct that the Fed will make a formal rate hike announcement on September 17 and the market could be correct that the announcement will lead to a rate rise of something less than 25 basis points.

Fed Funds – Targeting A Market That Barely Exists

In the July 29-30, 2014 FOMC minutes, the Fed said:

Almost all participants agreed that it would be appropriate to retain the federal funds rate as the key policy rate, and they supported continuing to target a range of 25 basis points for this rate at the time of liftoff and for some time thereafter.

On its face this sounds like a statement of the obvious, but it does represent a significant challenge for the Fed. As a 2014 New York Fed study noted, the fed funds market is drying up. The next set of charts shows fed funds market volume has decline about 75% since the financial crisis.