- Bloomberg – The Study Europe’s Rate-Setters Should Read

A new paper shows why the longer rates stay low, the fewer benefits they bring.

A key argument for hurrying up with a monetary tightening is that negative rates have hurt bank profitability, restricting lenders’ ability to give credit to families and firms. But is it really the case? How low can interest rates go before they become a drag on the economy? A new way of thinking about this problem comes from a working paper by Markus Brunnermeier and Yann Koby at Princeton University. The two scholars believe there is a “reversal interest rate” below which a central bank prompts lenders to cut back on their lending, instead of increasing it. This boundary creeps up over time, setting a limit to how long central banks should keep interest rates low. - Bloomberg – The Fed Needs a Better Inflation Target

A higher goal, with more public support, would benefit the central bank and the economy.

Today, a group of economists published a letter urging the U.S. Federal Reserve to consider a monumental change in policy: raising its target for inflation above the current 2 percent.I signed the letter. Here’s why.

The inflation target helps define how much stimulus the Fed can deliver when it lowers interest rates to zero (a boundary below which the central bank has been unwilling to go). In a higher-inflation environment, a nominal fed funds rate of zero results in a lower real, net-of-anticipated-inflation rate — the rate that economists typically see as most relevant for consumer and business decisions. If, for example, people expect inflation to be 3 percent, then a zero nominal rate translates into a negative 3 percent real rate — a full percentage point lower than the Fed could achieve if expected inflation were 2 percent.

Comment

So the Federal Reserve’s steadfast committal to interest rate hikes may be the better path barring a significant shift in economic data. However the added pace of tightening created by balance sheet reduction may be better connected to a higher inflation threshold as suggested by Kocherlakota.

The chart below shows the impact of year-over-year balance sheet reduction on deposits and lending during varying rates of inflation. We are aiming to show the likelihood of the Fed going too far (i.e. mistake) when tightening. This model uses changes in major economic data releases to determine probabilities of balance sheet reduction forcing our composite of deposits and lending to exceed +1 standard deviation from the long-term average (above green band in the first chart above). For the probabilities below we have held constant current rates of economic growth and assumed a pace of hikes at 50 bps per year.

Current core inflation near 1.9% year-over-year (CPI ex-food and energy) shows the Fed has a higher probability of causing a contraction in deposits and lending at nearly any pace of balance sheet reduction. Inflation running above 2.2% indicates a better environment with lower probabilities of contraction.

Conclusion

The Fed will be taking a gamble with continued rate hikes in hopes economic growth remains stable and inflation rises. Losing this bet would likely force the U.S. Treasury yield curve flatter and flatter while demand remains high for longer-dated issues. We have recently shown the yield curve is on the precipice of flattening to quite unfavorable levels for banks and other financials. In this scenario, the Fed like Chistopher Walkin has a fever and the only prescription is ‘more inflation.’

Next Wednesday (June 14) we will see May’s CPI. We continue to believe inflation remains paramount to job growth as we reach full employment.

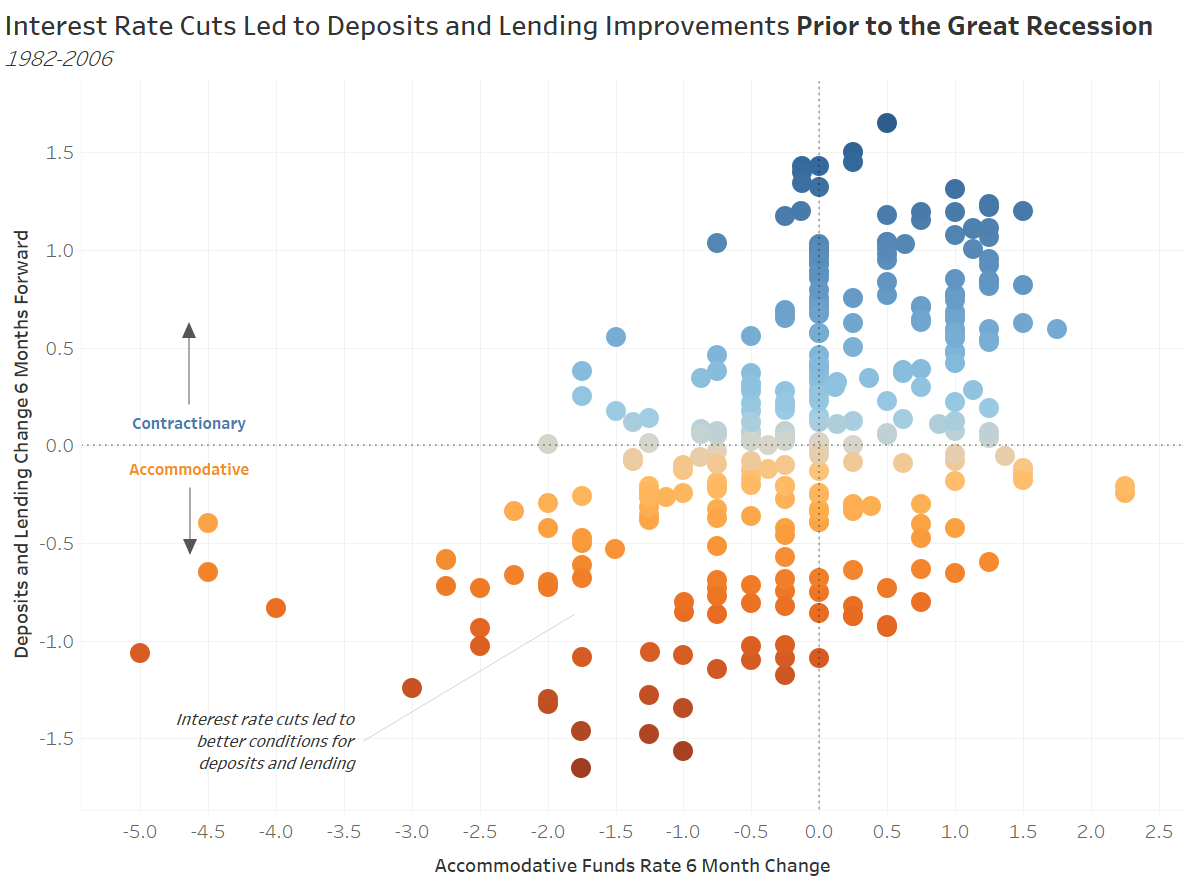

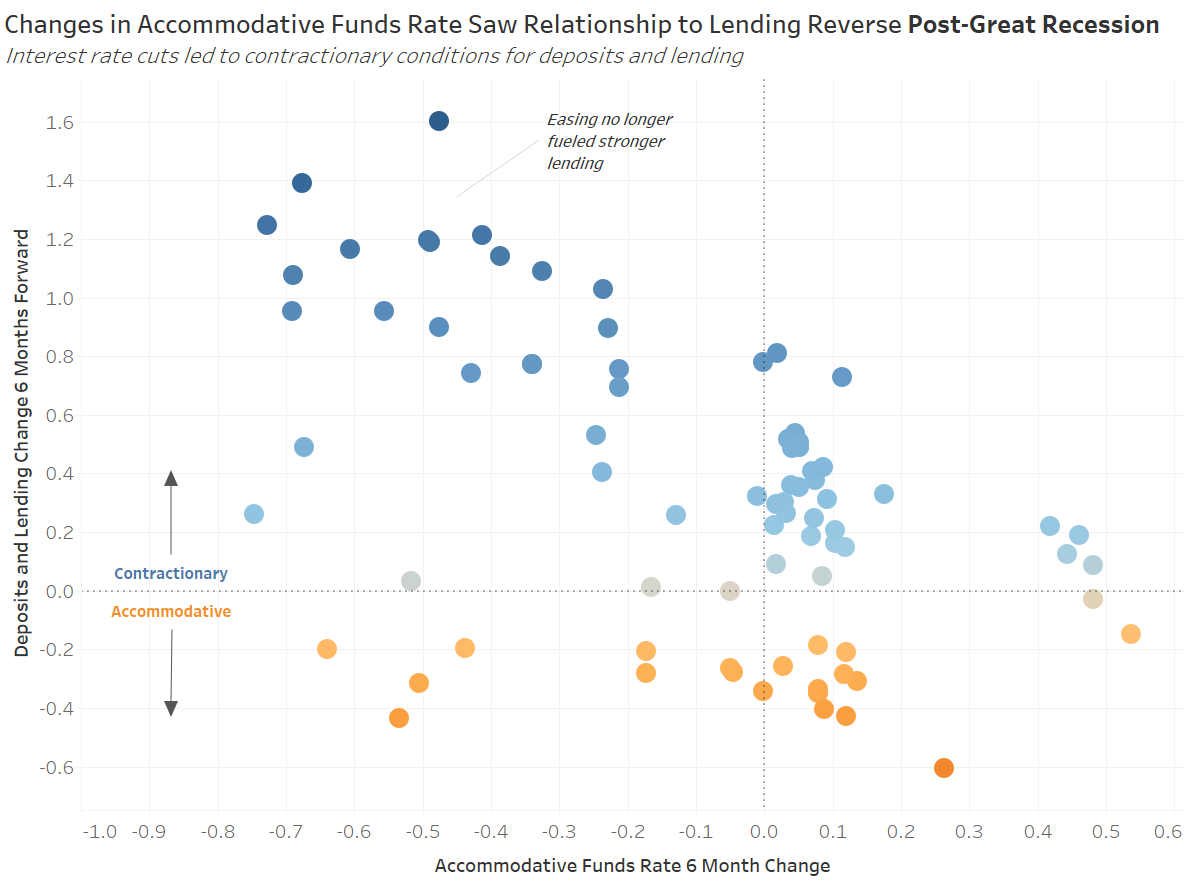

We have two opposing perspectives in the articles above concerning further monetary stimulus. The ‘reversal rate’ suggests interest rate cuts can move from an accommodative to contractionary impact on lending. The research indicates balance sheet expansion increases this so called reversal rate, meaning interest rate cuts could more quickly become ineffective. In contrast, Kocherlakota continues his support for easier policy by signing a letter with fellow economists urging the Federal Reserve to increase its inflation target.

Who’s right? Unfortunately, the camp calling for continued accommodative policy has a difficult battle showing its ability to foster improved lending and ultimately economic/inflation growth. However, both perspectives appear to have value. We will explain.

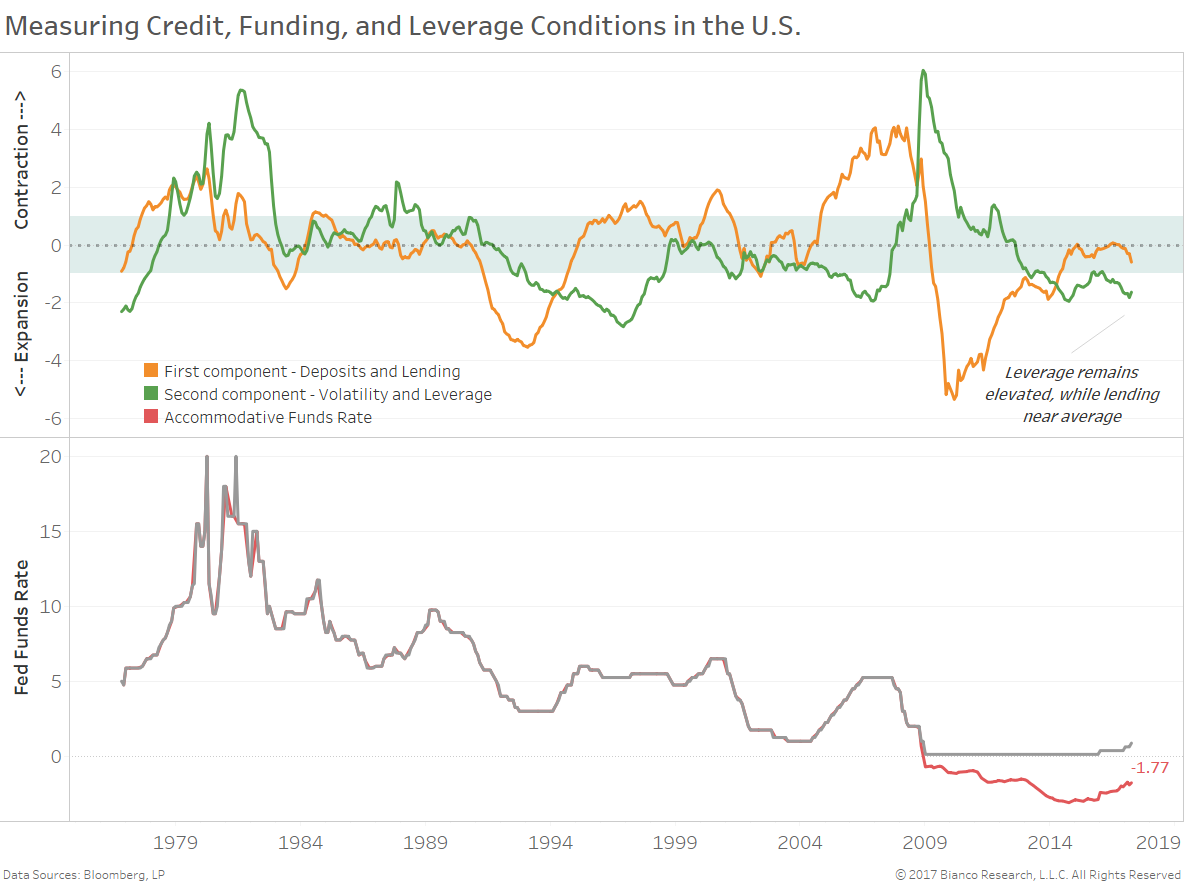

The chart below shows two important components of financial conditions: 1) deposits and lending growth (orange line) and 2) leverage and volatility in the financial system (green line). Lower levels indicate expansion, while higher levels contraction.

Financial leverage remains as elevated as ever and coupled with ultra-low volatility in market returns. Conversely, growth in deposits and lending has steadily retreated post-Great Recession to near average levels. We define values below the shaded green band as too expansionary and values above too contractionary. The Federal Reserve should likely aim for these financials conditions to remain near average (zero).