<Click on chart for larger image>

- The Financial Times – Reasons to fear a ‘triple taper tantrum’

Central banks have no contingency plan for a revival of growth

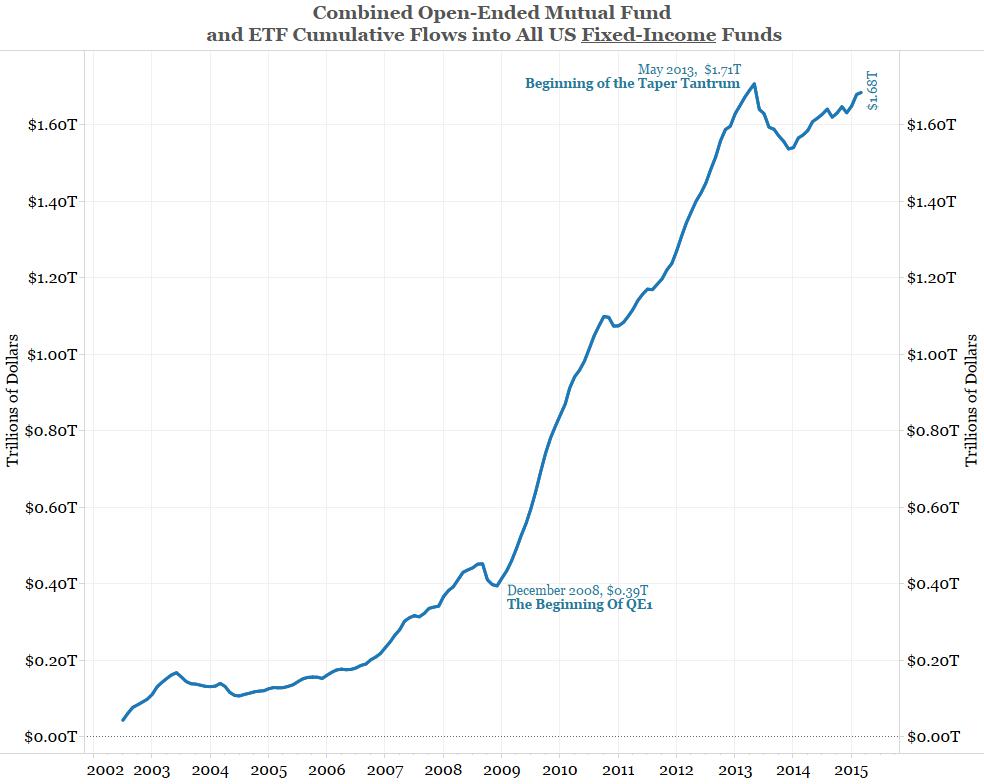

The “taper tantrum” during summer 2013 was a chastening exercise in exit communication. Since then, not only the Federal Reserve but also other central banks with enlarged balance sheets have been careful not to provide any reason for markets to overreact. The removal of monetary accommodation, as it becomes appropriate for each economy, is likely to be extremely gradual. Together, a gradual exit and careful communication should rule out the risk of another taper tantrum that could disrupt financial markets — at least that is what central banks and most investors expect. Why then are we worried not just about a taper tantrum but a “triple taper tantrum”? Because central banks do not have a contingency plan for success. Even partial success — stabilisation of growth rather than an outright revival — could be enough to derail their best-laid plans for a smooth exit from excessive monetary accommodation. Specifically, a combination of data in the US that are good enough to warrant policy rate rises and a stabilisation of growth in the euro area and Japan will probably be enough to raise the risk of a triple taper tantrum. Let’s run through this argument in three stages. First, what are the chances of growth in the G3 economies matching the profile that could spark a triple taper tantrum? US data have been weak, but may be taking a turn for the better. Rather than spending the oil windfall, consumers saved most of it. Recent surveys suggest they had little confidence oil prices would remain low, and held back consumption as a result. If oil prices do not rebound much further, conviction that the windfall is permanent would probably lead to improved consumption.

- The Wall Street Journal – Grand Central: The Untaper Tantrum

One of the more puzzling aspects of a puzzling week in Europe’s financial markets is that investors have acted as if the European Central Bank had signaled it might taper its bond-purchase program, when it fact it did the opposite. To recap: last week, the ECB left policy unchanged. During his regular news conference, ECB President Mario Draghi said investors should get used to volatility. Already on the climb going into the news conference, yields on German government bonds surged, while stocks fell. Nobody is entirely sure why this happened, although my colleague Richard Barley has drawn some interesting conclusions from the episode, which we might dub the “untaper tantrum” to distinguish it from the jump in U.S. Treasury yields of 2013 that followed Fed hints it would start winding down its bond purchases. What was overlooked was a firming up of the ECB’s commitment to do whatever it takes to hit its inflation target. Mr. Draghi said the central bank had not been at all surprised by the return to inflation in May, even though some policy makers had forecast a lengthier brush with deflation. Then he signaled that policy makers had been a little underwhelmed by recent signals on growth–there were signs of “some loss of momentum.” And Mr. Draghi then said it may be necessary to increase the scale of the bond-buying program, known to many as quantitative easing, or QE.

- MarketWatch.com – Why bonds are the most important asset class

If you want to make the most money, you should invest in stocks. But if you want to keep the money you made in stocks, you should invest in bonds. It’s ironic, but true: The most important asset class, bonds, is the one that has the lowest expected rate of return. At their core, bonds are quite simple. Yet decade after decade, investors tie themselves in rational and emotional knots trying to deal with bonds. These days, most people are concerned that interest rates will soon rise. (This has been the case for much of the past 20 years, by the way.) Most investors know that higher interest rates will mean lower bond prices. So how can it make sense to buy bonds now? Actually, it makes very little sense right now to buy or own bonds in the hope that you’ll be able to sell them later at a higher price. And that’s exactly the problem that gets investors into trouble. They think that if you can’t sell an investment at a profit, that investment is a bum deal. However, the truth is this: Making a profit isn’t why you should own bonds. For an analogy, think about an automobile. The reason to own a car is to go places. As everybody knows, that requires an engine. The moneymaking engine in most portfolios is made up of equities. But would you drive a car that had no brakes? I doubt it. Bonds are like the brakes in a car. The analogy is imperfect, but the point is valid. Like the brakes in a car, bonds let you control the risk of owning equities.

Comment

<Click on table for larger image>

The chart below shows the worst one-year total return declines in history. The thick brown line shows the decline since January 30 (top axis). The thick blue line shows the worst total return decline ever (2008/2009). Also on the chart are the 2013 taper tantrum (black), the carry trade unwind of 1994 (red), Volcker’s Saturday Night Massacre in 1979 (green) and Greenspan’s “considerable period” decline of 2003 (pink). The current selloff is right in line with these historic total return declines. We cannot wait to see what the second half of the year brings!

Does this volatility mean the end of the bull market? Not necessarily. It did not in 1994, 2003, 2008 and 2013. In all these cases the market eventually recovered all those losses. As the chart below shows, some of them did so in less than a year.

How wild has this year been? Dan Fuss of Loomis Sayles started in the bond business almost 50 years ago. It is probable that Loomis also hired some newly minted college graduate in the summer of 2014. When both of them talk about the biggest rallies and declines they have seen in their career, they could very well both pick January 2015 (rally) and the current decline. When asked about the wildest day they have ever seen, again both could pick the bond yield flash crash of October 15, 2014.

<Click on chart for larger image>

In our conference call two weeks ago titled Bond Volatility … Get Used To It (transcript, webcast/audio) we discussed how lengthening durations and extreme positioning are setting up the bond market for big bouts of volatility.

This volatility began earlier this year when January was one of the 30-year Treasury’s best total return months in history (detailed here).